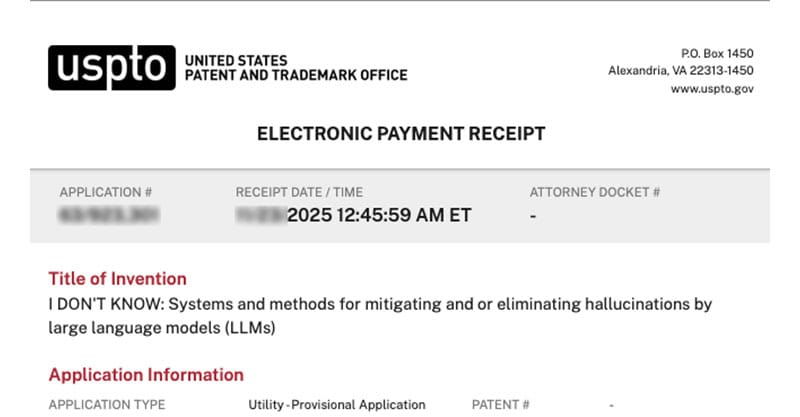

Systems and methods for mitigating and/or eliminating hallucinations by large language models (LLMs)

Modern societies depend on complex information systems to make decisions in finance, health care, law, education, transportation, logistics, defense, and everyday life. In all of these domains, there is a long-standing expectation that people and systems will acknowledge uncertainty, limits, or incapacity rather than guess. In human settings, phrases like “I don’t know” or “I can’t do that” signal an explicit boundary: the speaker is refusing to fabricate an answer or perform an action that would be unsafe, misleading, or outside their competence.

By contrast, many contemporary AI systems are built on probabilistic language models that are designed to always produce an output. These systems are trained to predict the next token or word that is statistically likely to follow a given input. In their default form, they have no inherent concept of “I don’t know” as an internal epistemic state. Instead, they tend to produce fluent, confident text even when the underlying training data does not support a reliable answer, or when a user’s request is outside the model’s true capability. This behavior has become widely known as “hallucination” or “confabulation,” and it has been documented across many model families and vendors.

Human decision makers have developed robust social norms around “I don’t know” and “I can’t.” In clinical practice, professional ethics rules require doctors to acknowledge uncertainty, seek a second opinion, or refer patients rather than speculate beyond their expertise. In aviation and other safety-critical industries, pilots and operators are trained to abort, divert, or declare “unable” in response to unsafe instructions from air traffic control and other authorities. In law and finance, fiduciary duties and professional codes of conduct explicitly require practitioners to refrain from making unsupported claims or engaging in actions beyond their competence. In all of these domains, a truthful admission of uncertainty is treated as a sign of professionalism and care, not weakness.

Historically, many technical systems have embodied an analogue of “I can’t” in the form of hard limits and circuit breakers. Mechanical governors were used in engines to prevent overspeeding and catastrophic failure by physically limiting how fast the engine could run. Electrical systems use fuses and breakers to interrupt current when loads exceed safe thresholds. Financial markets deploy trading halts and “limit down” rules to pause trading during extreme volatility. In each case, the system is designed to stop rather than continue in a dangerous regime. These design patterns reflect a basic engineering principle: when the cost of a wrong action is high, it is better to decline or defer than to proceed blindly.

Large language models and other generative systems operate very differently. They are usually deployed with a combination of safety training, prompt-level guardrails, and content filters intended to prevent certain categories of output, such as hate speech, explicit violence, or self-harm instructions. These measures often take the form of pattern-matching filters, manually crafted policies, or reinforcement learning from human feedback that penalizes unsafe or undesirable responses. The result is that models sometimes reply with refusal language such as “I can’t help with that” or “I’m not able to provide this information.”

However, these refusal behaviors are typically implemented as surface-level patterns, rather than as a deeply governed, auditable “I don’t know” or “I can’t” reflex anchored in clear policy and state. The same model that refuses one harmful prompt may provide unsafe content in response to a slightly rephrased or obfuscated prompt. Attackers and ordinary users alike have repeatedly demonstrated “jailbreaks” that circumvent guardrails by exploiting weaknesses in prompt-based controls and pattern filters. The underlying generative model continues to produce plausible text; a separate layer merely tries to stop certain outputs from reaching the user.

Existing approaches also struggle with the difference between “I don’t know” and “I won’t.” Many current systems are better at blocking clearly prohibited categories of content than at acknowledging genuine gaps in knowledge or capability. When a user asks about obscure facts, novel scientific claims, or specific personal information, models frequently guess or approximate instead of transparently admitting uncertainty. Similarly, when a user requests an action that is technically impossible or cannot be carried out by the AI system—such as performing a real-world transaction, accessing private records, or providing legal representation—the system may respond with approximated advice or speculative guidance instead of a clear statement that it cannot perform the requested task.

These behaviors create several tightly coupled problems. First, they erode user trust. End users often interpret the fluency and detail of an AI’s answer as evidence of correctness, especially when they lack expertise in the subject matter. When the answer is wrong but presented confidently, users may accept it, act on it, or repeat it, spreading misinformation further. Second, they complicate accountability. When an AI system fabricates references, invents sources, or misstates facts, it is difficult for downstream stakeholders to reconstruct what happened, who should have intervened, and whether proper safeguards existed. Third, they create regulatory and legal exposure in fields where accurate information is critical, such as health care, finance, education, or advice to vulnerable populations.

The risk is particularly acute for children, teens, and other vulnerable users. When these users seek help for sensitive issues such as anxiety, bullying, self-harm, or abuse, there is a strong expectation that any system they interact with will avoid making unfounded claims or giving potentially dangerous advice. If an AI system responds with an authoritative tone but incorrect or ungrounded information, the harm can be immediate and severe. In such cases, a truthful “I don’t know the answer” or “I can’t safely advise you on this” response, paired with a referral to real-world resources, may be far safer than a plausible but unverified answer.

Current safety frameworks rarely treat “I don’t know” and “I can’t” as first-class outcomes with explicit design, metrics, and governance. Instead, developers often aim to reduce hallucinations indirectly by improving training data, aligning objectives, and fine-tuning models. These measures can lower the rate of obvious errors but do not guarantee that the model will decline to answer when it should. Moreover, because many evaluation benchmarks reward models for coverage and completeness, there can be a subtle incentive to answer more questions rather than fewer.

In addition, most deployed systems lack a transparent, auditable record of when and why an AI model declined to answer or refused an action. Standard logging may capture raw prompts and outputs, but it does not always record the internal reasoning or policy checks that led to a refusal or a mistaken answer. This makes it difficult for operators to demonstrate to regulators, courts, or internal risk committees that the system has a robust mechanism for acknowledging uncertainty and for declining high-risk actions. It also hinders continuous improvement, because developers cannot easily study patterns in where the system should have said “I don’t know” or “I can’t” but did not.

The distinction between knowledge limits and capability limits is also blurred in many systems. A model may have adequate training data to answer a question accurately but lack the right tools or permissions to apply that knowledge in a user’s specific context. For example, a system might know how to format a legal document but lack the authority to file it, or it might understand general medical guidance but lack the ability to access a patient’s medical history or local regulations. In such cases, the system should distinguish between knowing about a topic in the abstract and being able to safely act on it in the real world.

Furthermore, existing refusal mechanisms are typically monolithic and static. They do not adapt dynamically to the risk level of the situation, the user’s identity or vulnerability, the downstream impact of being wrong, or evolving regulatory requirements. A generic “I can’t help with that” may be over-protective in low-risk contexts and under-protective in high-risk ones. There is no widely adopted architecture that systematically ties “I don’t know” or “I can’t” responses to structured policies, risk scoring, context state, and immutable records that can be audited and improved over time.

In everyday human interaction, “I don’t know” and “I can’t” are also temporally dynamic. A person might say “I don’t know yet” while they look up an answer, or “I can’t safely do that given the current information,” inviting the other party to provide more detail or to adjust the request. This flexible interplay between refusal, inquiry, and eventual action is a cornerstone of responsible collaboration. Current AI systems do not consistently support such conversational patterns in a governed way. They may either answer prematurely, or they may refuse outright without guiding the user to a safer or more actionable alternative.

As AI systems become more deeply embedded in critical infrastructure, business workflows, consumer products, and public services, regulators and standard-setting bodies are increasingly focused on transparency, accountability, and safety. Policymakers are beginning to ask how often AI systems produce hallucinations, how those events are detected and mitigated, and whether the systems can provide reliable, auditable evidence that they decline to answer or act when risk is high or knowledge is insufficient. There is growing recognition that a mature AI ecosystem requires not just powerful generative capabilities but also disciplined mechanisms for abstention, deferral, and refusal.

In summary, the current state of AI deployment exhibits a structural gap between how humans and engineered safety systems handle uncertainty, and how modern generative AI systems behave. Humans and traditional safety mechanisms have well-understood ways to say “I don’t know” or “I can’t,” backed by norms, training, and physical or logical constraints. Generative AI, on the other hand, is optimized to always say something, and its refusal behaviors are typically thin policy layers over a model that continues to generate output even when it should abstain. There is a clear need for architectures that treat “I don’t know” and “I can’t do that” as governed, measurable, first-class outcomes in AI systems, rather than as occasional byproducts of ad hoc safety training.

This is the complete BACKGROUND section of the SPECIFICATION.