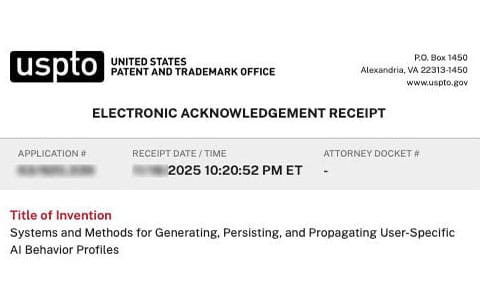

Systems and Methods for Generating, Persisting, and Propagating User-Specific AI Behavior Profiles

The present disclosure relates generally to digital assistants and human–computer interaction, and more specifically to systems and methods for capturing, persisting, and enforcing user preferences and policies governing assistant behavior, including in voice-driven interfaces.

State of the Art

Over the past decade, digital assistants have become widely deployed across smartphones, smart speakers, personal computers, vehicles, and other connected devices. Commercial examples include voice-activated assistants integrated into mobile operating systems, cloud-backed smart speakers, in-car infotainment systems, and productivity software helpers.

These assistants typically provide speech-driven access to a set of functions such as setting timers and alarms, playing music, retrieving information from the web, controlling connected devices, sending messages, or initiating calls. A broadly similar pipeline is found across platforms: wake-word detection, automatic speech recognition (ASR), natural-language understanding (NLU) for intent classification and slot extraction, orchestration of downstream services or “skills,” and templated text-to-speech (TTS) output.

Despite their ubiquity, these systems are generally perceived by users as useful only for a narrow set of simple, low-risk tasks. More sophisticated or sensitive tasks—such as complex multi-step workflows, configuration, or actions with financial or reputational impact—are rarely delegated to current assistants.

2.1 Historical Lineage: From Clippy to Siri/Alexa to LLM-Era Assistants

Early assistants

Clippy (Microsoft Office Assistant, 1997–2003) attempted proactive help based on hard-coded rules (“It looks like you’re writing a letter…”). It was iconic but widely regarded as intrusive, annoying, and impossible to govern. Users could not “teach” it anything meaningful about desired behavior.

Earlier text agents like ELIZA and PARRY demonstrated early conversational interaction but were brittle and limited.

Smartphone era

Siri (2011) on the iPhone 4S introduced mainstream speech recognition + natural-language intent handling. Google Now/Assistant, Cortana, and Bixby followed.

These systems followed a consistent architecture: ASR → NLU → intent routing → templated responses.

Smart speakers and IoT

Amazon Alexa (2014) turned assistants into always-listening household devices, followed by Google Home/Nest and HomePod.

By 2024, billions of voice-assistant devices were in global use, with high daily usage among smart-speaker owners.

The LLM era

Every major platform is now converging on “LLM + voice”:

• Apple Intelligence + Siri

• Google Gemini replacing Google Assistant

• Microsoft Copilot voice

• Amazon’s new LLM Alexa

• ChatGPT / GPT-4o real-time voice

Despite this technical progress, usage patterns remain shaped by a decade of unreliable voice experiences.

Limitations of Voice Recognition

A central limitation of the state of the art is the lack of truly reliable voice recognition.

Commercial ASR systems remain far from 100% accurate in real-world, diverse conditions. Accuracy drops with background noise, accents, non-standard diction, domain-specific vocabulary, and other variability. Even modest error rates cause:

• Changed meanings

• Wrong actions

• Spurious activations

• Follow-up questions

• Erosion of trust

Speech-recognition systems have documented demographic bias; some groups experience significantly higher error rates. To these users, voice recognition feels systematically untrustworthy.

As a result, many users limit voice assistants to trivial tasks where failure is inconsequential. Imperfect recognition has become a major barrier to adoption for consequential tasks.

Additional empirical evidence from mainstream studies

Studies show major assistants frequently struggle with:

• Medication names (Siri ≈ 78% accuracy; Alexa ≈ 64% in controlled studies)

• Accent and dialect variance (word-error-rate nearly double for some demographics)

• Multi-speaker or noisy environments

Users do not distinguish between ASR failures and NLU failures; both reduce perceived reliability.

Lack of User-Controlled Governance

Current assistants are governed by:

• Fixed rules by system architects

• Opaque ML models

• Sparse, static settings pages

• A handful of toggles or opt-outs

End users cannot:

• Express high-level natural-language governance preferences

• Convert corrections (“don’t do that again”) into durable policies

• Override or refine assumptions internally

• Define cross-device or cross-vendor behaviors

• Teach consistent behavior in the moment of interaction

When assistants misbehave, users typically repeat, rephrase, or give up. There is no simple in-flow mechanism to say:

“Here is how I want you to operate in situations like this, from now on.”

Thus system-level governance resides almost entirely with platform owners, not end users.

Historical reinforcement

Clippy’s inability to learn created the first wave of user frustration. Siri/Alexa’s inability to generalize user corrections deepened the same theme: users cannot govern assistant behavior.

Fragmented and Ephemeral Preferences

Existing preference mechanisms are:

• Fragmented across apps, devices, and ecosystems

• Mostly ephemeral

• Non-compositional — cannot form general rules

Examples include default music providers, notification settings, or per-device permissions, which often:

• Do not propagate

• Cannot be generalized

• Are hard to adjust in-flow

Assistants therefore repeat rejected behaviors such as:

• Choosing an undesired app

• Asking redundant follow-up questions

• Surfacing unwanted content

• Speaking aloud when silence is preferred

This lack of persistent, user-authored governance erodes trust and increases user frustration.

Adoption Patterns and Voice Assistant Stagnation

Multiple large-scale studies converge on the same picture:

• Assistants are widely known, widely tried, but shallowly used.

• Most usage remains confined to trivial tasks (weather, timers, music).

• Longitudinal studies show usage declines over time.

• Many users abandon smart speakers or restrict usage drastically.

Smartphone-assistant usage is even more fragile: in some surveys, the majority of users have tried Siri, but very few use it regularly. Trust and satisfaction scores are low.

The core reasons:

• Persistent recognition errors

• Perceived “lack of understanding”

• Difficulty handling nuanced requests

• Lack of user governance

• Privacy concerns

• Social awkwardness using voice in public

These experiences formed a decade-long negative bias against voice interaction.

Consequently, even as LLM-powered assistants become more capable, users default to typing.

- Impact on Adoption of Voice-Driven and LLM-Based Assistants

While modern LLM-driven assistants (Gemini, GPT-4o, Apple Intelligence Siri, LLM-Alexa, Copilot) are far more capable, their adoption is slowed by:

- Negative transfer from past experiences

Users assume new voice interfaces will fail the same way old ones did. Many no longer attempt voice for complex tasks.

- Rollout friction

LLM voice modes are often in preview, staged, limited, or gated due to safety and scaling concerns.

- Trust and safety concerns

Highly realistic voices, including controversies around voice likeness or misuse, create hesitation.

- Persistent technical issues

Even with advanced models, real-world ASR still struggles with noise, accents, and multiple speakers.

- No governance layer

End users still cannot give durable, natural-language instructions that change system behavior globally.

Thus, voice + LLMs have not yet overcome the structural barriers imposed by the earlier generation of assistants.

Summary of Key Deficiencies in the State of the Art

Across both the legacy assistant generation and the LLM-enhanced generation, the field continues to suffer from two persistent deficiencies:

- Voice recognition that is substantially less than 100% accurate in diverse, real-world usage.

- A lack of user-controlled, persistent governance mechanisms.

These deficiencies compound each other: unreliable recognition plus no governance means users have no way to correct or stabilize assistant behavior over time.

Resulting Gap

There remains a need for systems and methods that provide:

- Near-frictionless, in-flow mechanisms for users to express feedback and preferences

- Automatic conversion of that feedback into durable, enforceable policies

Cross-device, cross-vendor persistence - A governance layer that empowers end users—not only system architects—to shape the behavior of digital and voice assistants

This is the complete BACKGROUND section of the SPECIFICATION.